28 May 2020

Comparisons

Books and films.

By Dan Moondance

Comparisons, comparisons. Don’t know about you but as I grow older I find myself comparing more bits of stuff stored away in my brain with newer bits as they come along. Not sure even Dominic Cummings would be able to find a clever way of helping these brain noises to self-isolate. So they keep bumping into one another and the comparisons keep on coming. And life is full of comparisons, isn’t it? Some people are luckier than others. Young versus old. Black versus white. Male versus female. Early on I was hopeful that one decent thing about this CV plague was that it didn’t discriminate. Whoever you were it might pick on you, ask Boris. But that last hope is now dashed. If you live in a poor area, or happen to be the wrong colour, or haven’t been as careful with your weight to height ratio as you ought to have been, then there’s more chance that it will finish you off. The New Normal is the same wretched old normal as it always was. (Though definitions of what is Normal do vary. Today I read this from George Osborne: “I watch Love Island. I love Ant and Dec. I have a season ticket at Chelsea. I am normal.”)

Back to comparisons. I remember from student days that an important comparison was that between film and book. It was a big excitement when you heard that a film version of Dr Zhivago or Women in Love or even The Great Gatsby would be coming to the screen. If nothing else, it improved your chances of pretending to have read the book when you hadn’t. Oh, you said to yourself, oh for a film version of War and Peace, think of the reading that would save! When the film eventually arrived, you and your mates watched it and you did your comparison – which was the better, film or book, though not much attempt to understand why – but you rarely went back to read the book, even if you hadn’t done so in the first place. What would be the point?

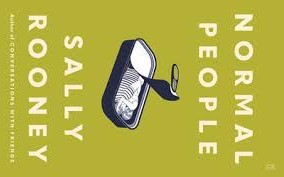

Recently, and appropriately in these times of the New Normal, a lot of us (including George Osborne presumably) will have been watching the serialised version of Sally Rooney’s Normal People. Also, a few weeks ago there was a Saturday evening rescreening of the film version of Julian Barnes’ The Sense of an Ending. In both cases I’ve discovered that watching the film version, however good or bad it was, made me want to go back and re-read the book, and with interesting results.

Sally Rooney was in her mid-twenties when she wrote Normal People; Julian Barnes in his early sixties when he did The Sense of an Ending. This is reflected in the different approach they take to their themes and subject matter, which are in a lot of ways quite similar. Normal People takes place in the present, over a period of four years which take the protagonists, Marianne and Connell, from their last six months at school (18-ish) to their last year at Trinity College, Dublin (22). Although the narrative is all in third person, what happens is portrayed only through the eyes of Marianne and Connell, in turn and shared equally. In The Sense of an Ending the narrative spans a much longer period, maybe fifty years, which takes the sole narrator and protagonist, Tony Webster, from his last years at school to the point in his later years when he receives a letter from a solicitor which unleashes the main part of the plot. And all these differences are reflected in the contrasting narrative styles adopted by the two authors.

Rooney’s prose has the urgency of youth. It is sparely written, short sentences mainly, a lot of concrete imagery but nothing flowery. Each sentence is carefully crafted, every word counts, as for instance in the first scene of the book, when Connell calls at Marianne’s house to collect his mother Lorraine, who is housekeeper to Marianne’ mother. First lines are always important and without aspiring to the profundity of an Austen or a Tolstoy, Rooney quietly manages to hit the right nail: “Marianne answers the door when Connell rings the bell.” Nothing pretentious about this. But it perfectly sums up the relationship that is about to unfold: bullied throughout her life, Marianne is imprisoned in her own insecurity and wants to escape from this, to open the door on a Normal Life, and she becomes dependent on Connell, the person who will help her to achieve this – whenever he rings her bell, she will surely answer it. Marianne has just got home from school, innocent no doubt, but already there is sign of her imminent awakening: “She’s still wearing her school uniform, but she’s taken off the sweater, so it’s just the blouse and skirt, and she has no shoes on, only tights.” Nothing prurient, but there is something very tantalising about a lady when she takes her shoes off. And then we meet Connell, who it will turn out is always to the point with his words, almost laconic. “Oh hey, he says.” That is all. She lets him in, and he comes down into the house. “He follows her, closing the door behind him.” House-trained then. Whereas privileged Marianne, who is in the middle of picking up an open jar of chocolate spread “in which she has left a teaspoon” is still really a child. And then, a few lines later we meet Lorraine, Connell’s single mother, a really lovely lady, who has finished her work and is getting ready to go home. She and Connell have a good and undemanding relationship: “Marianne was telling me you got your mock results today, Lorraine says.” No sign of recrimination for Connell not telling her first. But Connell is already uneasy about the social gap which exists between Marianne and himself, something which will form a wedge between them as the plot develops: “Then Lorraine starts unclipping her hair. To Connell this seems like something she could accomplish in the car.” At least he respects his mother enough not to say it out loud.

The point of all this is that Rooney’s book is written in a very cinematic way. The little actions and gestures of the characters that point to the way they behave and think are all there, almost waiting for the camera to roll. The dialogue is terse and always, always says what it means. The props are carefully laid out – the chocolate spread, the items of clothing – the different things that the characters eat and drink and wear at different times all have a bearing. There are no gaps to be filled. So it is hardly surprising that the TV serialisation has been rapturously received, all it needed was good performances from Daisy Edgar-Jones and Paul Mescal and these it surely got. As I reread the book, halfway through the TV serialisation, nothing seems out of place.

How different then to watch the film version of The Sense of an Ending several weeks ago. The acting is brilliant. Jim Broadbent at his most curmudgeonly, Charlotte Rampling at her most remote, and (Dame) Harriet Walter giving us a foretaste of the dry irony which now flowers so killingly in Killing Eve. The rambling elegance of Barnes’ prose is always something I have admired but here it expresses itself mainly through the thought processes of Tony Webster, very difficult to translate to the big screen other than through voice over. The pitch and graceful rhythm of Jim Broadbent’s voice are perfectly matched to this: “You get towards the end of life – no, not life itself, but of something else: the end of any likelihood of change in that life. You are allowed a long moment of pause, time enough to ask the question: what else have I done wrong?” But to balance the thoughtful introspection of the voice over there needs to be a coherent plot that develops evenly through the course of the narrative, and sad to say plotting is not Barnes’ strong point.

The plot, briefly stated, is this: Tony Webster, safely divorced and running a camera shop, has lived an unspectacular life. He is shaken out of his complacency by a solicitor’s letter which promises him a legacy from the recently deceased mother of his first girlfriend, Veronica. The legacy mainly consists of the diary of Adrian, the charismatic school friend who had taken up with Veronica after Tony and she had parted and then, for a reason not known, had committed suicide. Veronica is now her mother’s executor, so he will have to negotiate with her to obtain his legacy. But instead of the diary she gives him a letter, childish but obscene, which he had written to Adrian when he had discovered that he was going out with Veronica. Could this have contributed in some way to Adrian’s suicide? Driven on by guilt, Tony is determined to persuade Veronica to hand over the diary, but in the end all he achieves is to meet Adrian’s handicapped son, who he assumes is Veronica’s child. But in fact Adrian had had an affair with Veronica’s mother, and the child came from that relationship. The trail of discovery that Tony has followed in pursuit of this knowledge has brought in its wake an unravelling of self-awareness that is both sad and remorseful. Barnes recounts all this through Tony, alternating between current action (the pursuit of Veronica, aided and abetted by his ex-wife Margaret, now a barrister) and past recall (mainly schooldays). This dry narrative is brought to life by some telling metaphors, most notably a trip to Minsterworth when he was a student to witness the Severn Bore: “I don’t think I can properly convey the effect that moment had on me. It wasn’t like a tornado… it was more unsettling because it looked and felt quietly wrong, as if some small lever of the universe had been pressed, and here, just for these minutes, nature was reversed, and time with it.” Moments like this show Barnes at his best, but how to make a film of it?

The answer is that in the film the flimsy plot is “boosted” by a new sub-plot concerning the assistance that Tony eventually but reluctantly gives to his daughter in a difficult pregnancy. Through this he rediscovers his relationship with his divorced wife, who rewards him at the end by buying him a new watch to replace the one that he has just broken – symbol of a new beginning? Does this add anything to the original story? Nothing whatsoever. Does it make the film more enjoyable than it could have been? Barely. Is any attempt made to visualise the potent symbolism of some of Barnes’ prose? Very little – the Severn Bore is missing altogether, which is a great pity – if nothing else he would have been a welcome addition to the Government’s daily virus briefing team.

But does a viewing of the film add in any way to a second reading of the novel? Well yes, in fact it does. You learn through comparison. As we all are at the moment.